As the financial markets heave and crash their way up and down day after day, the defensive investor can take control of the chaos. Your very refusal to be active, your renunciation of any pretended ability to predict the future, can become your most powerful weapons. By putting every investment decision on autopilot, you drop any self-delusion that you know where stocks are headed, and you take away the market’s power to upset you no matter how bizarrely it bounces.

As Graham notes, “dollar-cost averaging” enables you to put a fixed amount of money into an investment at regular intervals. Every week, month, or calendar quarter, you buy more—whether the markets have gone (or are about to go) up, down, or sideways. Any major mutual fund company or brokerage firm can automatically and safely transfer the money electronically for you, so you never have to write a check or feel the conscious pang of payment. It’s all out of sight, out of mind.

The ideal way to dollar-cost average is into a portfolio of index funds, which own every stock or bond worth having. That way, you renounce not only the guessing game of where the market is going but which sectors of the market—and which particular stocks or bonds within them—will do the best.

Let’s say you can spare $500 a month. By owning and dollar-cost averaging into just three index funds—$300 into one that holds the total U.S. stock market, $100 into one that holds foreign stocks, and $100 into one that holds U.S. bonds—you can ensure that you own almost every investment on the planet that’s worth owning. Every month, like clockwork, you buy more. If the market has dropped, your preset amount goes further, buying you more shares than the month before. If the market has gone up, then your money buys you fewer shares. By putting your portfolio on permanent autopilot this way, you prevent yourself from either flinging money at the market just when it is seems most alluring (and is actually most dangerous) or refusing to buy more after a market crash has made investments truly cheaper (but seemingly more “risky”).

According to Ibbotson Associates, the leading financial research firm, if you had invested $12,000 in the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index at the beginning of September 1929, 10 years later you would have had only $7,223 left. But if you had started with a paltry $100 and simply invested another $100 every single month, then by August 1939, your money would have grown to $15,571! That’s the power of disciplined buying—even in the face of the Great Depression and the worst bear market of all time.

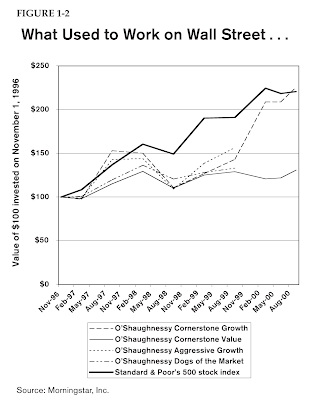

Figure 5-1 shows the magic of dollar-cost averaging in a more recent bear market.

Best of all, once you build a permanent autopilot portfolio with index funds as its heart and core, you’ll be able to answer every market question with the most powerful response a defensive investor could ever have: “I don’t know and I don’t care.” If someone asks whether bonds will outperform stocks, just answer, “I don’t know and I don’t care”—after all, you’re automatically buying both. Will health-care stocks make high-tech stocks look sick? “I don’t know and I don’t

care”—you’re a permanent owner of both. What’s the next Microsoft?

“I don’t know and I don’t care”—as soon as it’s big enough to own, your index fund will have it, and you’ll go along for the ride. Will foreign stocks beat U.S. stocks next year? “I don’t know and I don’t care”—if they do, you’ll capture that gain; if they don’t, you’ll get to buy more at lower prices.

By enabling you to say “I don’t know and I don’t care,” a permanent autopilot portfolio liberates you from the feeling that you need to forecast what the financial markets are about to do—and the illusion that anyone else can. The knowledge of how little you can know about the future, coupled with the acceptance of your ignorance, is a defensive investor’s most powerful weapon.

From the end of 1999 through the end of 2002, the S & P 500-stock average fell

relentlessly. But if you had opened an index-fund account with a $3,000 minimum investment and added $100 every month, your total outlay of $6,600 would have lost 30.2%—considerably less than the 41.3% plunge in the market.

Better yet, your steady buying at lower prices would build the base for an explo-

sive recovery when the market rebounds.

As Graham notes, “dollar-cost averaging” enables you to put a fixed amount of money into an investment at regular intervals. Every week, month, or calendar quarter, you buy more—whether the markets have gone (or are about to go) up, down, or sideways. Any major mutual fund company or brokerage firm can automatically and safely transfer the money electronically for you, so you never have to write a check or feel the conscious pang of payment. It’s all out of sight, out of mind.

The ideal way to dollar-cost average is into a portfolio of index funds, which own every stock or bond worth having. That way, you renounce not only the guessing game of where the market is going but which sectors of the market—and which particular stocks or bonds within them—will do the best.

Let’s say you can spare $500 a month. By owning and dollar-cost averaging into just three index funds—$300 into one that holds the total U.S. stock market, $100 into one that holds foreign stocks, and $100 into one that holds U.S. bonds—you can ensure that you own almost every investment on the planet that’s worth owning. Every month, like clockwork, you buy more. If the market has dropped, your preset amount goes further, buying you more shares than the month before. If the market has gone up, then your money buys you fewer shares. By putting your portfolio on permanent autopilot this way, you prevent yourself from either flinging money at the market just when it is seems most alluring (and is actually most dangerous) or refusing to buy more after a market crash has made investments truly cheaper (but seemingly more “risky”).

According to Ibbotson Associates, the leading financial research firm, if you had invested $12,000 in the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index at the beginning of September 1929, 10 years later you would have had only $7,223 left. But if you had started with a paltry $100 and simply invested another $100 every single month, then by August 1939, your money would have grown to $15,571! That’s the power of disciplined buying—even in the face of the Great Depression and the worst bear market of all time.

Figure 5-1 shows the magic of dollar-cost averaging in a more recent bear market.

Best of all, once you build a permanent autopilot portfolio with index funds as its heart and core, you’ll be able to answer every market question with the most powerful response a defensive investor could ever have: “I don’t know and I don’t care.” If someone asks whether bonds will outperform stocks, just answer, “I don’t know and I don’t care”—after all, you’re automatically buying both. Will health-care stocks make high-tech stocks look sick? “I don’t know and I don’t

care”—you’re a permanent owner of both. What’s the next Microsoft?

“I don’t know and I don’t care”—as soon as it’s big enough to own, your index fund will have it, and you’ll go along for the ride. Will foreign stocks beat U.S. stocks next year? “I don’t know and I don’t care”—if they do, you’ll capture that gain; if they don’t, you’ll get to buy more at lower prices.

By enabling you to say “I don’t know and I don’t care,” a permanent autopilot portfolio liberates you from the feeling that you need to forecast what the financial markets are about to do—and the illusion that anyone else can. The knowledge of how little you can know about the future, coupled with the acceptance of your ignorance, is a defensive investor’s most powerful weapon.

From the end of 1999 through the end of 2002, the S & P 500-stock average fell

relentlessly. But if you had opened an index-fund account with a $3,000 minimum investment and added $100 every month, your total outlay of $6,600 would have lost 30.2%—considerably less than the 41.3% plunge in the market.

Better yet, your steady buying at lower prices would build the base for an explo-

sive recovery when the market rebounds.