But trading as if your underpants are on fire is not the only form of speculation. Throughout the past decade or so, one speculative formula after another was promoted, popularized, and then thrown aside.

All of them shared a few traits—This is quick! This is easy! And it won’t hurt a bit!—and all of them violated at least one of Graham’s distinctions between investing and speculating. Here are a few of the trendy formulas that fell flat:

Cash in on the calendar. The “January effect”—the tendency of small stocks to produce big gains around the turn of the year— was widely promoted in scholarly articles and popular books published in the 1980s. These studies showed that if you piled into small stocks in the second half of December and held them into January, you would beat the market by five to 10 percentage

points. That amazed many experts. After all, if it were this easy, surely everyone would hear about it, lots of people would do it, and the opportunity would wither away.

What caused the January jolt? First of all, many investors sell their crummiest stocks late in the year to lock in losses that can cut their tax bills. Second, professional money managers grow more cautious as the year draws to a close, seeking to preserve their outperformance (or minimize their underperformance). That makes them reluctant to buy (or even hang on to) a falling stock.

And if an underperforming stock is also small and obscure, a money manager will be even less eager to show it in his year-end list of holdings. All these factors turn small stocks into momentary bargains; when the tax-driven selling ceases in January, they typically bounce back, producing a robust and rapid gain.

The January effect has not withered away, but it has weakened.

According to finance professor William Schwert of the University of Rochester, if you had bought small stocks in late December and sold them in early January, you would have beaten the market by 8.5 percentage points from 1962 through 1979, by 4.4 points from 1980 through 1989, and by 5.8 points from 1990 through 2001.

As more people learned about the January effect, more traders bought small stocks in December, making them less of a bargain and thus reducing their returns. Also, the January effect is biggest among the smallest stocks—but according to Plexus Group, the leading authority on brokerage expenses, the total cost of buying and selling such tiny stocks can run up to 8% of your investment.11 Sadly, by the time you’re done paying your broker, all your gains on the January effect will melt away.

Just do “what works". In 1996, an obscure money manager named James O’Shaughnessy published a book called What Works on Wall Street. In it, he argued that “investors can do much better than the market.” O’Shaughnessy made a stunning claim: From 1954 through 1994, you could have turned $10,000 into $8,074,504, beating the market by more than 10-fold—a towering 18.2% average annual return. How? By buying a basket of 50 stocks with the highest one-year returns, five straight years of rising earnings, and share prices less than 1.5 times their corporate revenues.12 As if he were the Edison of Wall Street, O’Shaughnessy obtained U.S. Patent No. 5,978,778 for his “automated strategies” and launched a group of four mutual funds based on his findings. By late 1999 the funds had sucked in more than $175 million from the public—and, in his annual letter to shareholders, O’Shaughnessy stated grandly: “As always, I hope that together, we can reach our long-term goals by staying the course and sticking with our time-tested investment strategies.”

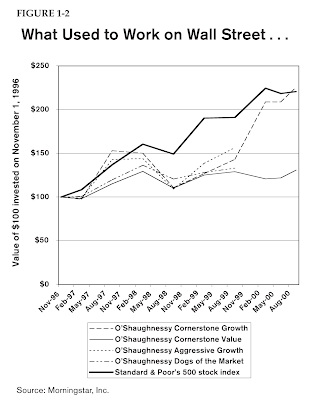

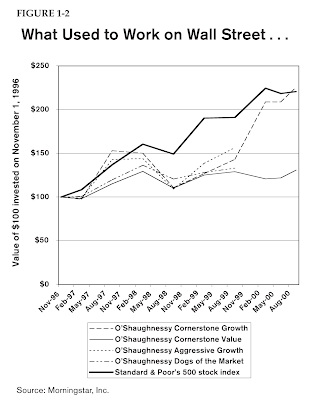

But “what works on Wall Street” stopped working right after O’Shaughnessy publicized it. As Figure 1-2 shows, two of his funds stank so badly that they shut down in early 2000, and the overall stock market (as measured by the S & P 500 index) walloped every O’Shaughnessy fund almost nonstop for nearly four

years running.

Follow “The Foolish Four”. In the mid-1990s, the Motley Fool website (and several books) hyped the daylights out of a technique called “The Foolish Four.” According to the Motley Fool, you would have “trashed the market averages over the last 25 years” and could “crush your mutual funds” by spending “only 15 minutes a year” on planning your investments. Best of all, this technique had “minimal risk.” All you needed to do was this:

1. Take the five stocks in the Dow Jones Industrial Average with the lowest stock prices and highest dividend yields.

2. Discard the one with the lowest price.

3. Put 40% of your money in the stock with the second-lowest price.

4. Put 20% in each of the three remaining stocks.

5. One year later, sort the Dow the same way and reset the portfolio according to steps 1 through 4.

6. Repeat until wealthy.

Over a 25-year period, the Motley Fool claimed, this technique would have beaten the market by a remarkable 10.1 percentage points annually. Over the next two decades, they suggested, $20,000 invested in The Foolish Four should flower into $1,791,000. (And, they claimed, you could do still better by picking the five Dow stocks with the highest ratio of dividend yield to the square root of stock price, dropping the one that scored the highest, and buying the next four.)

Let’s consider whether this “strategy” could meet Graham’s definitions of an investment:

• What kind of “thorough analysis” could justify discarding the stock with the single most attractive price and dividend—but keeping the four that score lower for those desirable qualities?

• How could putting 40% of your money into only one stock be a “minimal risk”?

• And how could a portfolio of only four stocks be diversified enough to provide “safety of principal”?

The Foolish Four, in short, was one of the most cockamamie stock-picking formulas ever concocted. The Fools made the same mistake as O’Shaughnessy: If you look at a large quantity of data long enough, a huge number of patterns will emerge—if only by chance. By random luck alone, the companies that produce above-average stock returns will have plenty of things in common.

But unless those factors cause the stocks to outperform, they can’t be used to predict future returns.

None of the factors that the Motley Fools “discovered” with such fanfare—dropping the stock with the best score, doubling up on the one with the second-highest score, dividing the dividend yield by the square root of stock price—could possibly cause or explain the future performance of a stock. Money Magazine found that a portfolio made up of stocks whose names contained no

repeating letters would have performed nearly as well as The Foolish Four—and for the same reason: luck alone. As Graham never stops reminding us, stocks do well or poorly in the future because the businesses behind them do well or poorly—nothing more, and nothing less.

Sure enough, instead of crushing the market, The Foolish Four crushed the thousands of people who were fooled into believing that it was a form of investing. In 2000 alone, the four Foolish stocks—Caterpillar, Eastman Kodak, SBC, and General Motors— lost 14% while the Dow dropped by just 4.7%.

As these examples show, there’s only one thing that never suffers a bear market on Wall Street: dopey ideas. Each of these so-called investing approaches fell prey to Graham’s Law. All mechanical formulas for earning higher stock performance are “a kind of self-destructive process—akin to the law of diminishing returns.” There are two reasons the returns fade away. If the formula was just based on random statistical flukes (like The Foolish Four), the mere passage of time will expose that it made no sense in the first place. On the other hand, if the formula actually did work in the past (like the January effect), then by publicizing it, market pundits always erode—and usually eliminate—

its ability to do so in the future. All this reinforces Graham’s warning that you must treat speculation as veteran gamblers treat their trips to the casino:

You must never delude yourself into thinking that you’re investing when you’re speculating.

Speculating becomes mortally dangerous the moment you begin

to take it seriously.

You must put strict limits on the amount you are willing to wager.

Just as sensible gamblers take, say, $100 down to the casino floor and leave the rest of their money locked in the safe in their hotel room, the intelligent investor designates a tiny portion of her total portfolio as a “mad money” account. For most of us, 10% of our overall wealth is the maximum permissible amount to put at speculative risk. Never mingle the money in your speculative account with what’s in your investment accounts; never allow your speculative thinking to spill over into your investing activities; and never put more than 10% of your assets into your mad money account, no matter what happens.

For better or worse, the gambling instinct is part of human nature— so it’s futile for most people even to try suppressing it. But you must confine and restrain it. That’s the single best way to make sure you will never fool yourself into confusing speculation with investment.

All of them shared a few traits—This is quick! This is easy! And it won’t hurt a bit!—and all of them violated at least one of Graham’s distinctions between investing and speculating. Here are a few of the trendy formulas that fell flat:

Cash in on the calendar. The “January effect”—the tendency of small stocks to produce big gains around the turn of the year— was widely promoted in scholarly articles and popular books published in the 1980s. These studies showed that if you piled into small stocks in the second half of December and held them into January, you would beat the market by five to 10 percentage

points. That amazed many experts. After all, if it were this easy, surely everyone would hear about it, lots of people would do it, and the opportunity would wither away.

What caused the January jolt? First of all, many investors sell their crummiest stocks late in the year to lock in losses that can cut their tax bills. Second, professional money managers grow more cautious as the year draws to a close, seeking to preserve their outperformance (or minimize their underperformance). That makes them reluctant to buy (or even hang on to) a falling stock.

And if an underperforming stock is also small and obscure, a money manager will be even less eager to show it in his year-end list of holdings. All these factors turn small stocks into momentary bargains; when the tax-driven selling ceases in January, they typically bounce back, producing a robust and rapid gain.

The January effect has not withered away, but it has weakened.

According to finance professor William Schwert of the University of Rochester, if you had bought small stocks in late December and sold them in early January, you would have beaten the market by 8.5 percentage points from 1962 through 1979, by 4.4 points from 1980 through 1989, and by 5.8 points from 1990 through 2001.

As more people learned about the January effect, more traders bought small stocks in December, making them less of a bargain and thus reducing their returns. Also, the January effect is biggest among the smallest stocks—but according to Plexus Group, the leading authority on brokerage expenses, the total cost of buying and selling such tiny stocks can run up to 8% of your investment.11 Sadly, by the time you’re done paying your broker, all your gains on the January effect will melt away.

Just do “what works". In 1996, an obscure money manager named James O’Shaughnessy published a book called What Works on Wall Street. In it, he argued that “investors can do much better than the market.” O’Shaughnessy made a stunning claim: From 1954 through 1994, you could have turned $10,000 into $8,074,504, beating the market by more than 10-fold—a towering 18.2% average annual return. How? By buying a basket of 50 stocks with the highest one-year returns, five straight years of rising earnings, and share prices less than 1.5 times their corporate revenues.12 As if he were the Edison of Wall Street, O’Shaughnessy obtained U.S. Patent No. 5,978,778 for his “automated strategies” and launched a group of four mutual funds based on his findings. By late 1999 the funds had sucked in more than $175 million from the public—and, in his annual letter to shareholders, O’Shaughnessy stated grandly: “As always, I hope that together, we can reach our long-term goals by staying the course and sticking with our time-tested investment strategies.”

But “what works on Wall Street” stopped working right after O’Shaughnessy publicized it. As Figure 1-2 shows, two of his funds stank so badly that they shut down in early 2000, and the overall stock market (as measured by the S & P 500 index) walloped every O’Shaughnessy fund almost nonstop for nearly four

years running.

Follow “The Foolish Four”. In the mid-1990s, the Motley Fool website (and several books) hyped the daylights out of a technique called “The Foolish Four.” According to the Motley Fool, you would have “trashed the market averages over the last 25 years” and could “crush your mutual funds” by spending “only 15 minutes a year” on planning your investments. Best of all, this technique had “minimal risk.” All you needed to do was this:

1. Take the five stocks in the Dow Jones Industrial Average with the lowest stock prices and highest dividend yields.

2. Discard the one with the lowest price.

3. Put 40% of your money in the stock with the second-lowest price.

4. Put 20% in each of the three remaining stocks.

5. One year later, sort the Dow the same way and reset the portfolio according to steps 1 through 4.

6. Repeat until wealthy.

Over a 25-year period, the Motley Fool claimed, this technique would have beaten the market by a remarkable 10.1 percentage points annually. Over the next two decades, they suggested, $20,000 invested in The Foolish Four should flower into $1,791,000. (And, they claimed, you could do still better by picking the five Dow stocks with the highest ratio of dividend yield to the square root of stock price, dropping the one that scored the highest, and buying the next four.)

Let’s consider whether this “strategy” could meet Graham’s definitions of an investment:

• What kind of “thorough analysis” could justify discarding the stock with the single most attractive price and dividend—but keeping the four that score lower for those desirable qualities?

• How could putting 40% of your money into only one stock be a “minimal risk”?

• And how could a portfolio of only four stocks be diversified enough to provide “safety of principal”?

The Foolish Four, in short, was one of the most cockamamie stock-picking formulas ever concocted. The Fools made the same mistake as O’Shaughnessy: If you look at a large quantity of data long enough, a huge number of patterns will emerge—if only by chance. By random luck alone, the companies that produce above-average stock returns will have plenty of things in common.

But unless those factors cause the stocks to outperform, they can’t be used to predict future returns.

None of the factors that the Motley Fools “discovered” with such fanfare—dropping the stock with the best score, doubling up on the one with the second-highest score, dividing the dividend yield by the square root of stock price—could possibly cause or explain the future performance of a stock. Money Magazine found that a portfolio made up of stocks whose names contained no

repeating letters would have performed nearly as well as The Foolish Four—and for the same reason: luck alone. As Graham never stops reminding us, stocks do well or poorly in the future because the businesses behind them do well or poorly—nothing more, and nothing less.

Sure enough, instead of crushing the market, The Foolish Four crushed the thousands of people who were fooled into believing that it was a form of investing. In 2000 alone, the four Foolish stocks—Caterpillar, Eastman Kodak, SBC, and General Motors— lost 14% while the Dow dropped by just 4.7%.

As these examples show, there’s only one thing that never suffers a bear market on Wall Street: dopey ideas. Each of these so-called investing approaches fell prey to Graham’s Law. All mechanical formulas for earning higher stock performance are “a kind of self-destructive process—akin to the law of diminishing returns.” There are two reasons the returns fade away. If the formula was just based on random statistical flukes (like The Foolish Four), the mere passage of time will expose that it made no sense in the first place. On the other hand, if the formula actually did work in the past (like the January effect), then by publicizing it, market pundits always erode—and usually eliminate—

its ability to do so in the future. All this reinforces Graham’s warning that you must treat speculation as veteran gamblers treat their trips to the casino:

You must never delude yourself into thinking that you’re investing when you’re speculating.

Speculating becomes mortally dangerous the moment you begin

to take it seriously.

You must put strict limits on the amount you are willing to wager.

Just as sensible gamblers take, say, $100 down to the casino floor and leave the rest of their money locked in the safe in their hotel room, the intelligent investor designates a tiny portion of her total portfolio as a “mad money” account. For most of us, 10% of our overall wealth is the maximum permissible amount to put at speculative risk. Never mingle the money in your speculative account with what’s in your investment accounts; never allow your speculative thinking to spill over into your investing activities; and never put more than 10% of your assets into your mad money account, no matter what happens.

For better or worse, the gambling instinct is part of human nature— so it’s futile for most people even to try suppressing it. But you must confine and restrain it. That’s the single best way to make sure you will never fool yourself into confusing speculation with investment.

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий